Understanding the microscopic world inside our bodies has become one of the most exciting frontiers in modern science. Discussions about health, immunity, mental health, and even chronic diseases increasingly revolve around the terms microbiome and microbiota. While these terms are often used interchangeably, they refer to distinct yet interconnected concepts. Clarifying the difference is crucial for understanding how they impact human health and why they are central to cutting-edge research in fields ranging from nutrition and medicine to mental health and longevity.

This article will explore the precise definitions of microbiome and microbiota, their roles in human health, and how they interact with each other. We’ll also cover recent scientific research, the implications for health, and practical applications in nutrition and medicine.

Defining the Terms

Microbiota: The Collection of Microorganisms

The term microbiota refers to the collection of microorganisms living in a specific environment. In the human body, the microbiota includes:

- Bacteria – the most studied and abundant members of the microbiota

- Viruses – including bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria)

- Fungi – such as Candida species

- Archaea – ancient microorganisms similar to bacteria

- Protists – single-celled organisms like Giardia

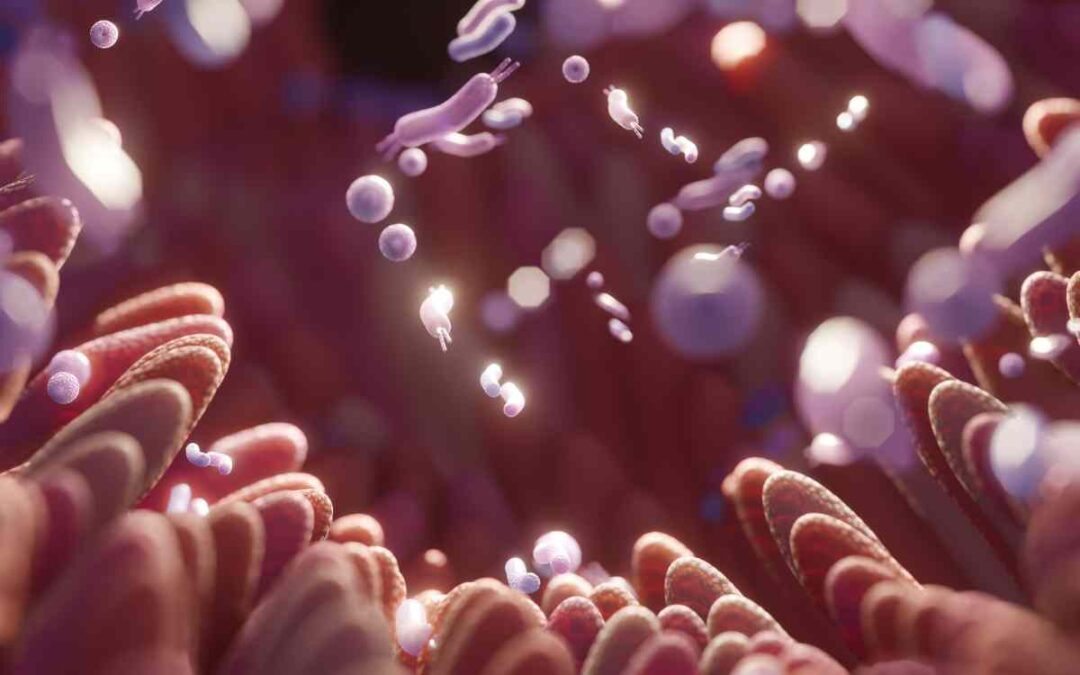

These organisms coexist and interact with each other, forming complex networks that influence the health of their host (in this case, humans). The human body houses trillions of microorganisms, with the majority residing in the gut, but they are also present on the skin, in the mouth, the respiratory tract, the urinary tract, and even in the placenta.

Example: The gut microbiota consists of over 1,000 bacterial species, with dominant phyla including Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes [1].

Microbiome: The Genetic Blueprint of the Microbiota

The microbiome refers to the collection of all the genetic material (genomes) of the microbiota. In other words, while the microbiota consists of the organisms themselves, the microbiome consists of their collective genes and genetic potential.

The human microbiome contains over 3 million genes, compared to about 20,000 genes in the human genome [2]. This massive genetic library encodes for proteins, enzymes, and metabolic functions that the human body cannot perform on its own, including:

- Digestion of complex carbohydrates and fibers

- Synthesis of vitamins (e.g., vitamin K, B12)

- Detoxification of harmful substances

- Modulation of the immune system

Example: Certain strains of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus produce lactic acid and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which regulate immune responses and gut barrier integrity.

How Microbiota and Microbiome Work Together

Although the microbiota and microbiome are distinct concepts, they are inherently linked. The microbiota provides the physical presence of microorganisms, while the microbiome reflects the functional capacity of these organisms.

A useful analogy is to think of a rainforest:

- The microbiota = the various species of plants, animals, and insects living in the rainforest.

- The microbiome = the genetic instructions that determine how those species function and interact.

Key Interactions Between Microbiota and Microbiome

- Metabolism – The microbiota metabolizes dietary fibers into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which influence energy metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and inflammation.

- Immune System Regulation – Certain bacterial species influence the production of anti-inflammatory or pro-inflammatory cytokines, shaping immune response.

- Neurotransmitter Production – The gut microbiota synthesizes neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine, influencing mood and behavior (the gut-brain axis).

- Detoxification – Bacteria metabolize environmental toxins and help eliminate them from the body.

- Nutrient Synthesis – The microbiota produces vitamins and other essential nutrients that the human body cannot synthesize alone.

How the Microbiome Affects Human Health

The microbiome is now considered a separate “organ” in the human body due to its essential role in health and disease. The genetic potential of the microbiome shapes several physiological functions:

1. Digestive Health

- The gut microbiota helps break down dietary fibers into SCFAs (like butyrate, acetate, and propionate), which nourish colon cells and maintain gut barrier integrity.

- A healthy microbiome prevents the overgrowth of harmful bacteria, reducing the risk of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and colorectal cancer [3].

2. Immune Function

- The microbiome “trains” the immune system by exposing it to antigens, helping to distinguish between harmless and harmful agents.

- A balanced microbiome reduces the risk of autoimmune diseases and allergies [4].

3. Mental Health

- The gut-brain axis connects the microbiome to brain function and mood regulation.

- Certain bacterial strains (e.g., Lactobacillus rhamnosus) produce gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which has a calming effect on the nervous system [5].

4. Metabolic Health

- The gut microbiome influences how calories are extracted from food and stored as fat.

- Disruptions in gut flora are linked to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome [6].

5. Cardiovascular Health

- Certain gut bacteria produce trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) from dietary choline, which has been linked to increased cardiovascular disease risk [7].

What Disrupts the Microbiota and Microbiome?

Several factors can disrupt the balance and diversity of the microbiota, leading to health problems:

- Antibiotics – Kill both harmful and beneficial bacteria, disrupting microbial balance.

- Diet – High sugar, low fiber, and processed food diets reduce bacterial diversity.

- Stress – Chronic stress alters gut permeability and microbiome composition.

- Cesarean Birth – Babies born via C-section have a different microbiota than those delivered vaginally.

- Formula Feeding – Breastfeeding provides beneficial prebiotics and bacteria.

Restoring and Maintaining a Healthy Microbiome

- Prebiotics – Non-digestible fibers that feed beneficial bacteria (e.g., inulin, fructooligosaccharides).

- Probiotics – Live beneficial bacteria (e.g., Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium) that improve gut health.

- Diverse Diet – Eating a variety of whole plant-based foods increases microbial diversity.

- Fermented Foods – Foods like yogurt, kefir, kimchi, and sauerkraut supply live bacteria.

- Stress Reduction – Mindfulness and stress reduction practices support a healthy gut-brain axis.

Conclusion

The terms microbiota and microbiome are closely related but distinct. The microbiota refers to the community of microorganisms residing in and on the human body, while the microbiome refers to the genetic material and metabolic potential of these organisms. Their interaction is essential for human health, affecting everything from digestion and immunity to mental health and metabolic function. By understanding these differences and nurturing a healthy microbiome through diet and lifestyle, we can unlock new pathways to better health and disease prevention.